“The ‘Amen!’ of Nature is always a flower.”

– Oliver Wendell Holmes

I have been reading so much about flowers lately and I want to teach you what I learned as well as what I know. So, I am going to teach about the flower in three parts. Part 1: The history, physiology and pattern of the flowers (to help you identify flowering plants). Part 2: Pollination and the sex life of flowers, and Part 3: The flower as a healing agent.

I have been reading so much about flowers lately and I want to teach you what I learned as well as what I know. So, I am going to teach about the flower in three parts. Part 1: The history, physiology and pattern of the flowers (to help you identify flowering plants). Part 2: Pollination and the sex life of flowers, and Part 3: The flower as a healing agent.

THE FLOWER – PART ONE

How did this happen. The flower is so different than any other tissue on the plant. The flower is a creation so beautiful and so attracting and it grows at the tip of the green or brown stem or branch of a plant. The flower is as intricately designed as if created to reflect the fractal formulas of the universe. The flower is designed to include color, shape, aroma, and chemical attractants to bring forth the pollinators so that it can complete its cycle of life: reproduction of itself. How beautiful and how perfect it seems to us humans too. But, how is it created? The answer is again found in the DNA of the plant and the meristem cells that drive the action in creating the plant. In this essay we are introduced to the Floral Meristem.

FLORAL MERISTEM

Last time we learned about the leaf. We learned that the leaf was formed by the action of chemical changes and apical meristem cells. The plant is reaching for the sun just as there is enough warmth, light, chemistry, moisture and food and creating new structures that will help it thrive.

The meristematic cells give rise to various organs of the plant, and keep the plant growing. The Shoot Apical Meristem (SAM) gives rise to organs like the leaves and flowers. When plants begin the developmental process known as flowering, the shoot apical meristem is transformed into an inflorescence meristem, which goes on to produce the floral meristem, which produces the familiar sepals, petals, stamens, and carpels of the flower. Floral meristem cells are responsible for determinate growth. That is, they know exactly what they are supposed to create and that is the flower. And, this flower will live long enought to reproduce the plant and then die. The floral meristem cells direct the limited growth of the flower to a particular size and form. The transition from shoot meristem to floral meristem requires floral meristem identity genes that both specify the floral organs and cause the termination of the production of stem cells at just the right time. The floral meristem identity genes are “turned on” at the time the leaf meristem is turned on. In fact some parts of flowers (bracts) are actually modified leafs. If you would like to learn more detail about this process please check out the wiki on Meristems located at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meristem

Queen Anne's Lace

THE HISTORY, PHYSIOLOGY AND PATTERN OF FLOWERS

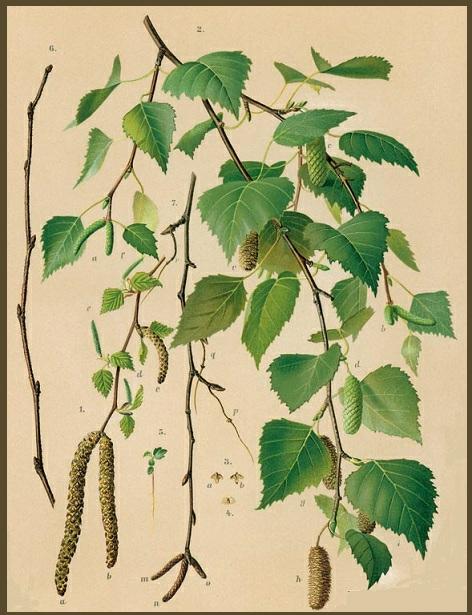

The ancestors of flowering plants diverged from gymnosperms around 245–202 million years ago, and the first flowering plants known to exist are from 140 million years ago. They diversified enormously during the Lower Cretaceous and became widespread around 100 million years ago, but replaced conifers as the dominant trees only around 60–100 million years ago. (Wikipedia)

Non-flowering plants includes conifers, ginkgoes, ferns, cycads, horsetails, and mosses

A Flower is the reproductive structure of a tree or other plant, consisting of at least one pistil or stamen, and often including petals and sepals. According to botanist Brian Capon the flower is a short branch bearing specially adapted leaves, and reproduction is the sole function for which flowers evolved.

A land plant that flowers is called an angiosperm. The Angiosperms are seed-producing plants like the gymnosperms and can be distinguished from the gymnosperms by a certain characteristics including flowers, endosperm within the seeds, and the production of fruits that contain the seeds.

Flowers aid angiosperms by enabling a wider range of adaptability and broadening the ecological niches open to them. This has allowed flowering plants to largely dominate terrestrial ecosystems.

There are an estimated 352,282 unique flowering plant names, it is also estimated that there are approximately 69,500 known species of monocots and 49,500 known species of non-monocot species. The number of presently unknown plant species is thought to be 10 to 20 per cent or 20,000 to 30,000 species (Joppa, Roberts, and Pimm 2010). The number of flowering monocot plants increased steadily for the last 250 years up until about 1850 when the number began to plateau. There has been a steady decline in the last 50 years of known species and there are still species that have not been discovered. The decline is due to habitat encroachment and environmental degradation.

MONOCOT VS DICOT – A REFRESHER

Monocot vs Dicot

Traditionally, the flowering plants have been divided into two major groups, or classes: the Dicots (Magnoliopsida) and the Monocots (Liliopsida). The Dicotyledon is typically described as group of flowering plants whose seed typically has two embryonic leaves or cotyledons. The monocotyledon is typically described as having one embryonic leaf.

The Dicotyledon class has the following characteristics: – two seeds, – netted veins in the leaves, usually tap-rooted, usually complex branching, – flower parts mostly patterned in 4’s and 5’s. Example of the dicotyledon flowers would be: buttercup, rose, gentian and aster.

Monocotyledon class has the following characteristics: – one seed leaf, – parallel veins in the leaves, – horizontal rootstalks, – usually simple branching – flower parts mostly in 3’s. Examples of the flowers would be: arrowhead, lily and orchid.

FLOWER PHYSIOLOGY

Flower physiology

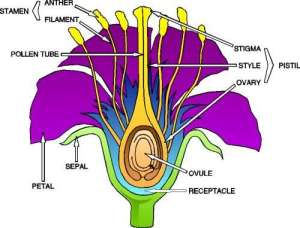

The parts of the flower are important to learn as the specific arrangement of flower parts will help you to identify a specific plant. There is a more complete list of flower parts with definitions at the end of this essay, but for now we will be focusing on petals, sepals, pistil, stamens, ovary, stigma, and style.

FLOWER PATTERNS OF SPECIFIC PLANT FAMILES

Mustard family – They have four free saccate sepals and four clawed free petals, staggered. The mustard family flower pattern includes 4 petals, 4 sepals, 4 tall stamens, 2 short stamens (Examples: Wild Mustard, Wall flower, Water Cress, Stock, Candytuft, and Lunaria)

The mints, taxonomically known as Lamiaceae or Labiatae – 5 united petals, (2 lobes up, 3 down), 5 untied sepals, 4 stamens (2 long, 2 short). Flower matures into a seed capsule containing four nutlets. (Examples: Horehound, Self Heal, Stinging Nettles, basil, mint, rosemary, sage, savory, marjoram, oregano, thyme, lavender, and perilla)

The Apiaceae (or Umbelliferae), commonly known as carrot or parsley family – 5 petals, 5 stamens, 2-cell ovary, compound umbels (Examples: angelica, anisewater hemlock, Water parsnip, Queen Anne’s lace, cow parsnip, parsnip, dill and fennel).

The Fabaceae or Leguminosae, commonly known as the legume, pea, or bean family – irregular flowers- 5 petals forming banner, wings and keel. The keel consists of two petals fused together. Internal fused and free stamen. Fabaceae range in habit from giant trees (like Koompassia excelsa) to small annual herbs, with the majority being herbaceous perennials. (Examples: wisteria, pea, bean, acacia, mimosa, vetch,

Lilly or Lilium family is a genus of herbaceous flowering plants growing from bulbs, all with large, prominent flowers. – Flowers with parts in three. Sepals and petals usually identical. 3 sepals, and 3 petals (same size and color), 6 stamens, Pistil with a 3-parted stigma. (Examples: Tiger lilly, Shasta Lilly, Leopard Lilly,

Malvaceae, or the mallow family, is a family of flowering plants containing over 200 genera with close to 2,300 species. 5 petals, 5 sepals, bracts (modified leaves located at bottom of the flower), numerous stamens fused together as a column, pistil. The ovary is superior, with axial placentation. Capitate or lobed stigma. The flowers have nectaries made of many tightly packed glandular hairs, usually positioned on the sepals. The flowers are commonly borne in definite or indefinite axillary inflorescences, which are often reduced to a single flower, but may also be cauliflorous, oppositifolious or terminal. (Examples: hollyhock, okra, globe mallow, Hibiscus)

Sunflower or Aster family is an exceedingly large and widespread family of vascular plants.[3] The group has more than 22,750 currently accepted species, spread across 1620 genera and 12 subfamilies. Composites of many small flowers in disk-like flowerhead. Stigmas, 5 stamens fused around pistil, 5 petals fused together, pappus hair sepals, ovary. Even the petals are individual flowers. Each seed is produced by a single tiny flower. Multiple layers of bracts are common. (Examples: Dandelion, sunflower, asters, dahlia, Chrysanthemum, Gerbera, Calendula, Dendranthema, Argyranthemum, Dahlia, Tagetes, Zinnia).

Rose family– Rosaceae (the rose family) are a medium-sized family of flowering plants, including about 2830 species in 95 genera. Roses can be herbs, shrubs or trees. Most species are deciduous, but some are evergreen.[2] They have a worldwide range, but are most diverse in the northern hemisphere. Arrangement of flowers is radially symmetrical and almost always hermaphroditic. Rosaceae generally have five sepals, five petals and many spirally arranged stamens. The bases of the sepals, petals, and stamens are fused together to form a characteristic cup-like structure called hypanthium. They can be arranged in racemes, spikes, or heads, solitary flowers are rare. (Examples of rose family includes many fruit varieties life apple, cherry, plum chokecherry as well as wild and domesticated roses)

There are several other families of flowers that I will explore in the future but for a full breakdown of all the flowering plant families check out Thomas Elpel’s book “Botany in a Day, The Pattern Method of Plant Identification”. He covers all the plant families including those I did not identify today such as : Heath family, Pyrola family, Indian Pipe family, Primrose family, Hydrangea family, Gooseberry family, Stonecrop family, Saxifrage family, Gentian, Dogbane, Milkweed, Nightshade, Morning Glory, Pholx, Waterleaf, Borage, Verbena, Plantain, Olive, Figwort, Broomrape, Bladderwort, Harebell, Madder, Honeysuckle, Teasel, Arrowhead, Arrow Grass, Water nymph, Pondweed, Spiderwort, Rush, Sedge, Grass, Cattail, Duckweed, Arum, Lily, Iris, and Orchid.

INFLORESCENCES – BRANCHING PATTERNS OF STEM OF THE FLOWER

An inflorescence is a group or cluster of flowers arranged on a stem that is composed of a main branch or a complicated arrangement of branches. Strictly, it is the part of the shoot of seed plants where flowers are formed and which is accordingly modified. The types of arrangements include: the spike, the raceme, the panicle, the umbel, the composite, the corium, capitulum and the thyrse. (Please see graphic of these patterns).

An inflorescence is a group or cluster of flowers arranged on a stem that is composed of a main branch or a complicated arrangement of branches. Strictly, it is the part of the shoot of seed plants where flowers are formed and which is accordingly modified. The types of arrangements include: the spike, the raceme, the panicle, the umbel, the composite, the corium, capitulum and the thyrse. (Please see graphic of these patterns).

VOCABULARY

- Anther: The anther is part of the stamen and produces the pollen.

- Articulation: Another term for articulation is internode. Articulation describes the space between two nodes (joints).

- Calyx:The whorl of sepals on the outside of a flower is referred to as the calyx.

- Corolla: The whorl of petals is called the corolla.

- Filament: The filament provides support for the anther in the stamen.

- Floral Axis: The floral axis is the stem holding the reproductive flower parts.

- Microsporangium: The microsprangium is located in the anther and produces microspores, which become male gametophytes. These male gametophytes will later be used in forming the pollen grains.

- Nectary: The nectary produces nectar, a sweet liquid that attracts insects and birds for feeding. As they drink the nectar, the nearby pollen sticks to them and is transported to other flowers.

- Ovary: The ovary houses the ovules and will become the fruit after pollination.

- Ovule: The ovules contain egg cells and become the seeds after pollination.

- Pedicel:The pedicel is the flower stalk.

- Perianth: The perianth is the collective term for the calyx and corolla.

- Petal: The petal is designed to attract pollinators to the flower and protect the stamen and pistil. Many have patterns that can be seen in ultraviolet light by bees and other insects. These indicate where the nectar is located.

- Pistil: The pistil is the female reproductive part in the flower. It includes the ovary, style, and stigma.

- Sepal: Sepals are found on the outside of the flower in a whorl. They are usually green. The group of sepals is called the calyx.

- Stamen: The stamen is the male reproductive organ in the plant. It consists of the anther and filament.

- Stigma: The stigma is the sticky surface where pollen lands and is collected to fertilize the ovules.

- Style: The style is part of the pistil and holds the stigma above the ovary.

REFERENCES

Capon, Brian (2010) Botany for Gardeners, 3rd edition, Timber Press, Portland, Oregon

Elpel, Thomas J. (2006) 5th Edition, Botany in a day. The Patterns Method of Plant Identification, Hops Press LLC, Pony, Montana

Lucas N. Joppa, David L. Roberts, and Stuart L. Pimm,(2010) How many species of flowering plants are there? Proceedings of the Royal Society of Biological Sciences, Proc. R. Soc. B doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.1004 Published online: http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/early/2010/07/07/rspb.2010.1004.full.pdf+html viewed online April 26, 2012

Wikipedia – Flowering plants – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flowering_plant Viewed on the internet on 4-28-2012

NEXT TIME: Pollination and the Sex Life of Flowers

Read Full Post »

‘And you? When will you begin that long journey into yourself?’ – Rumi