As they presented the herb to me they told me to drop it on the earth and when it hit the earth it took root and flowered. You could see a ray of light coming up from the flower, reaching the heavens, and all the creatures of the universe saw the light. – Black Elk (in DeMaille, The Sixth Grandfather)

Ok, being the total plant nerd that I am; I get very excited about teaching about parts of the plant. I mean it blows my mind that all you have to do is cut a branch, place it in water, and watch it grow roots. How does that happen? What would happen if humans could do the same and just grow new parts? (clue: stem cells)

And, a second amazing fact about stems and branches is that you can graft a branch of one plant on to another plant and promote new and interesting growth and fruit. Pure magic! (More on grafting later).

What is happening here? It all goes back to the most magical part of a plant-the “meristem cell”. You know, the God-particle magical cell that stores all the DNA of the plant and allows parts of the plant to regenerate, accept cells from other plants, and grow itself from an injured part.

Let me explain in more detail. (Now don’t get bored with all this plant physiology facts, in the end it all is just amazing and your knowledge of living with, growing and ingesting plants will grow exponentially!)

Meristem tissue in most plants consists of undifferentiated meristematic cells. With the apical meristem cells the tissue either heading downward and becoming roots or heading upwards and becoming stem, branch, leaves and flower are considered to be indeterminate or undifferentiated, in that they do not possess any defined end fate. The meristem cells “remember” that they are going to grow into a tree, a shrub, a wildflower etc, but allow a variety of changes to happen to the tissue. Where ever these cells appear in the plant, there can be new growth, including growing new parts. These types of cells seem to store the DNA of any part of the plant. The apical meristem, or growing tip, is a completely undifferentiated meristematic tissue found in the buds and growing tips of roots in plants. Its main function is to begin growth of new cells in young seedlings at the tips of roots and shoots (forming buds, among other things). Meristem cells cause the plant growth to take place in a very organized yet adaptive process. Now, meristem cells can become differentiated after they divide enough times and reach a node or internode. As the plant grows upward driven by apical meristem cells the tissue begins to organize itself into stem, branch, leaves and flower. These cells divide rapidly and are found in zones of the plant where much growth can take place. That is why you can graft one part of a plant to another part of the plant if it is in the right zone or node and if the two plants share the same type of DNA. Plants must be closely related for grafting to be successful.

For tissues to knit successfully, the cambium layers (full of fast dividing meristem cells) and rootstock must be brought into firm contact. The cambium – a continuous narrow band of thin-walled, regenerative cells just below the bark or rind – grows to form a bridge or union between the two parts in days. The same cells are found at the joint of a branch which allows it to grow new roots at the cut. Now, not all plants can grow roots from a branch. You need to study each plant for its particular characteristics.

SEED TO STEM – THE JOURNEY BEGINS

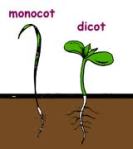

The stem begin its journey with the seed opening up and a dicot or monocot leaf revealing itself.

A monocot (a flowering plant that produces an embryo seed with single cotyledons) will produce only one leaf. A dicot will produce two embryonic seed leaves or cotyledon. The cotyledon is a seed leaf – the first to appear as the seed sprouts. It appears at the same time that root tissue appears.

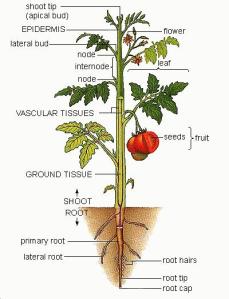

Next a shoot appears (new stem) and sends out growth. The apical meristem cell structure is leading the way. We assume that the stem is heading upward toward light but a contradiction to this rule would be stems that spread downward or sideways like potatoes, tulip bulbs and other tubers. A strawberry plant will create a “stolon” or sideways stem to propagate new growth. A vine has a long trailing stem that grows along the ground or along anything it can attach to.

The three major internal parts of a stem are the xylem, phloem, and cambium. The xylem and phloem are the major components of a plant’s vascular system. A cambium is a lateral meristem that produces secondary tissues by cell division. The cambium area is located just under the epithelial (outer most area of the stem) and is very active in cell growth. It is this area that is tapped into when attempting grafting.

The three major internal parts of a stem are the xylem, phloem, and cambium. The xylem and phloem are the major components of a plant’s vascular system. A cambium is a lateral meristem that produces secondary tissues by cell division. The cambium area is located just under the epithelial (outer most area of the stem) and is very active in cell growth. It is this area that is tapped into when attempting grafting.

Stem tissue is actually organized into pipe-like vascular bundles held together by pith and cortex tissues. These tissues are used for pipelines of fluid transport, connecting leaves, stems and roots. They also serve as a supportive structure for the stem. The stem is also made up of other substances that allow it to remain flexible so that it will not break easily. Depending on what kind of plant is growing, a great tree or a wildflower, the stem may become a thick trunk with layers of vascular cambium, cork and hard bark or a more herbaceous plant. The trunk of a tree is its main stem. And, yes plants can have more than one stem. The stem that branches is called a branch.

Stems may be long, with great distances between leaves and buds (branches of trees, runners on strawberries), or compressed, with short distances between buds or leaves (fruit spurs, crowns of strawberry plants, dandelions). All stems must have buds or leaves present to be classified as stem tissue.

An area of the stem where leaves are located is called a node. Nodes are areas of great cellular activity and growth, where auxiliary buds develop into leaves or flowers. The area between nodes is called the internode. Nodes are protected when pruning back a plant. Destruction of the nodes can result in long non-fruiting branches.

MODIFIED STEMS

Although typical stems are above-ground trunks and branches, there are modified stems which can be found above and below the ground. The above-ground modified stems include crowns, stolons, and spurs and the below-ground stems are bulbs, corms, rhizomes, and tubers.

STEM FUNCTION

- Stems serve as conduits (pipelines) for carrying water and minerals from the roots upward to the leaves utilizing the xylem tissue and for carrying food from the leaves (where food is manufactured through the process of photosynthesis) down to the roots utilizing the phloem tissue.

- Stems provide support for the leaves and reproductive structures (flowers, fruit, and seeds) of the plant.

- Stems are also used for food storage (as in potatoes and onions) and in plants with herbaceous (green-colored) stems they help manufacture food just as the leaves do.

NATIVE PLANT PROPAGATION BY CUTTINGS.

Taking cuttings from native plants to propagate them is especially helpful in preserving what is left of many species. There is no digging or destroying plants. Forest communities are not damaged.

The process of removing a plant part then having that part grow into a genetically exact replica of the original plant is called cutting propagation. It is a plant cloning technique. The plant part that is removed is called a cutting. Plants can be propagated from root cuttings, leaf cuttings, stem cuttings, etc.

- The mother plant or “stock” plant should be at a stage of growth most likely to have stem cuttings root. Old, mature plants are often more difficult to root than young, vigorously growing plants. Using new growth on a mature plant may not root. Always try to use young plants.

- Always place cuttings in water as soon as it is cut. You can wrap the cut end of a cutting in wet paper towels and place in plastic bags if you do not have a tub of water. If the cutting wilts it may not fully recover and may not develop roots.

- Always take cuttings when the temperature is above freezing. Research has demonstrated that cuttings collected when temperatures were above freezing and stored in plastic bags or moist burlap in a refrigerator rooted in higher percentages than fresh, unstored cuttings taken when shoots were frozen.

- For all types of stem cuttings, the cuttings should be removed with a clean, sharp (don’t crush stems) knife or pruners and placed into a container that will keep the cutting from losing more moisture.

Some amazing Cascadian bioregion native plants that root from branches are: Pacific Willow (Salix lucida), Hooker’s Willow (Salix hookeriana), Pacific Ninebarks (Physocarpus capitatus), and Snowbush (Ceanothus velutinus). All are great attractors of important pollinators and Snowbush will fix nitrogen in the soil.

The first peoples of Cascadia built summer fishing and hunting huts along marshes and streams by placing freshly cut Willow in circles. The Willow would root and grow into a shelter and hunting blind. Today, some wonderful garden trellis have been erected using live Willow.

The first peoples of Cascadia built summer fishing and hunting huts along marshes and streams by placing freshly cut Willow in circles. The Willow would root and grow into a shelter and hunting blind. Today, some wonderful garden trellis have been erected using live Willow.

VOCABULARY

- Angiosperms – A plant that has flowers and produces seeds enclosed within a carpel. The angiosperms are a large group and include herbaceous plants, shrubs, grasses, and most trees.

- Bud – an undeveloped or embryonic shoot and normally occurs in the axil of a leaf or at the tip of the stem. Recognizing buds is important under two circumstances when trying to identify plants. 1) When you need to distinguish a bud from a “stipule”, and 2) When you need to determine whether a leaf is “simple” or “compound”.

- Cotyledon – A seed leaf. A leaf of the embryo of a seed plant, which upon germination either remains in the seed or emerges, enlarges, and becomes green.

- Crowns – is a region of compressed stem tissue from which new shoots are produced, generally found near the surface of the soil. Crowns (strawberries, dandelions, African violets) are compressed stems having leaves and flowers on short internodes.

- Dicot –comprising seed plants (angiosperms) that have two cotyledons in their seed. Examples of dicots flowering plants are (more 300 families) sunflowers, peas, geranium, rose, magnolias, maples, oaks and willows.

- Internode – the part of a plant stem between two of the nodes from which leaves emerge.

- Monocot – comprising seed plants that produce a seed embryo with a single cotyledon and parallel-veined leaves: includes grasses and lilies and palms and orchids; divided into four subclasses or super orders: Alismatidae; Arecidae; Commelinidae; and Liliidae. flowering plant; the stem grows by deposits on its inside

- Node – the part of a plant stem from which one or more leaves emerge, often forming a slight swelling or knob. Something special happens at a node that tells the plant tissue to start forming leaves and flowers.

- Pith – The soft, spongelike, central cylinder of the stems of most flowering plants, composed mainly of parenchyma (in higher plants, any soft tissue consisting of thin-walled, relatively undifferentiated living cells)

- Spur – is a compressed fruiting branch. Spurs are short, stubby, side stems that arise from the main stem and are common on such fruit trees as pears, apples, and cherries, where they may bear fruit. If severe pruning is done close to fruit-bearing spurs, the spurs can revert to a long, nonfruiting stem.

- Stipule – One of the usually small, paired appendages at the base of a leafstalk in certain plants, such as roses and beans.

- Stolon – is a horizontal stem that is fleshy or semi-woody and lies along the top of the ground. A runner is a type of stolon. It is a specialized stem that grows on the soil surface and forms a new plant at one or more of its nodes. Strawberry runners are examples of stolons. Remember, all stems have nodes and buds or leaves. The leaves on strawberry runners are small but are located at the nodes which are easy to see. The spider plant also has stolons.

REFERENCES

- Capon, Brian (1990) (Revised 3rd edition, 2005) Botany for Gardeners, Timber Press, Portland, London

- Gunther, Erna. (1945) (Revised 1973) Ethnobotany of Western Washington. Knowledge and use of Indigenous plants by Native Americans, University of Washington Press.

- Pojar & McKinnon, (1994) Plants of the Pacific Northwest Coast, Washington, Oregon, British Columbia & Alaska, Lone Pine Publishing, Vancouver, British Columbia

- Toogood, Alan (1999) Plant Propagation, American Horticultural Society, DK Publishing, Inc. New York, NY