There are places on the earth where everything is in balance. Places where the boundaries between humans and nature disappear. Upon entrance to these natural places the human spirit leaves the cloak of ego, struggle, separateness and the tension of the world falls away.

There are places on the earth where everything is in balance. Places where the boundaries between humans and nature disappear. Upon entrance to these natural places the human spirit leaves the cloak of ego, struggle, separateness and the tension of the world falls away.

The Hoh rainforest on the most westerly edge of the Olympic Peninsula in Washington State is such a place.

“Come to the woods, for here is rest. There is no repose like that of the green deep woods. Here grow the wallflower and the violet. The squirrel will come and sit upon your knee, the logcock will wake you in the morning. Sleep in forgetfulness of all ill. Of all the upness accessible to mortals, there is no upness comparable to the mountains.” John Muir — John of the Mountains: The Unpublished Journals of John Muir, (1938), page 235.

I entered the Hoh Rainforest twice in 2013. I am only now writing about my experiences because something changed in me and I could not find the words to describe the emotions that welled up in me. Something lost, something found. I had a realization that we may be at a point of desolation in Western Civilization. We are destroying the places where our souls can find rest at an alarming pace. And, I feel helpless in stopping this destruction. And I am a refugee of those killing fields.

In spite of recognizing that the Hoh Rainforest may be all that is left of the rainforests of the west coast, my visits to the Hoh Rainforest helped me reconnect with my life purpose and develop a strong still voice, one with boundaries and courage.

I grew up near the coast range mountains in Western Oregon. At that time the rainforests were intact from British Columbia to Northern California. The habitat of animal and plant life was diverse and interconnected through that area. The ecology of the place provided shelter not only for the millions of species who lived there, but for the land east of the region. You see those precious rainforests created moisture for an area that spanned thousands of miles into the mid-west. Those precious rainforests seeded the clouds that came first from the ocean and passed over the area and dropped moisture on the Cascade Mountains, the Rocky Mountains and then finally fell and fed the great aquifers of the mid-west. Now the water is missing and the forests are burning. The water wars have begun and wildlife is going extinct.

Strong words, yes I know. Maybe you came to this blog for a description of a walk in the woods. Maybe you thought I would teach you about the native plants and fungi I saw. I will. I know. I saw. But for now you need to learn why my heart froze for an entire year.

Like I said, I grew up in Oregon. Millions of acres of Oregon’s forests, both public and private, have been clearcut over the past century. The devastation to wildlife, ecosystems, cloud ecology and snowpack reserves in the region is wide-spread and unrepairable. I realize I grew up and lived in a war zone. I am deeply scared by what I have experienced.

When I entered the Hoh Rain Forest I was both renewed and filled with much sorrow. The place was Eden and I was a guest of the Great Creator who loves us all. And yet the visits brought home to me what has been lost, and what is being lost.

And now, with that preface let us journey together.

Oh how I wish you and I were actually on the trail through the Hoh. I am not a good enough writer to use words to describe the musky smell of the deep forest or the phenomenal song of the forest Robin . All I know is that when I breathe in, my body, mind and spirit remember something older than civilization. The merging of flora, fauna, fungi, fresh air, local air currents, wind, rain, caverns of the tangled roots of an ancient Big Leaf Maple, Sitka Spruce and Western Hemlock create a wondrous natural world experience.

Receiving 12 to 14 feet of rain per year, the Hoh Rainforest is one of the best examples of temperate rainforest in the world. The Hoh Rainforest that is intact is located within the Olympic National Park and is protected from devastation. The Hoh River valley was formed thousands of years ago by glaciers. Between the park boundary and the Pacific Ocean, 48 km (30 mi) of river, much of the forest has been logged within the last century, although many pockets of forest remain.

I choose my hiking partners well. I expected a long drive and then another long hike. I wanted someone who could become part of the forest and was somewhat introspective. I was not interested in timed excursions or a mapped out day hikes. I wanted to let the forest lead me.

The first time I entered the Hoh Rainforest it was very early April 2013. The wild flowers had not yet opened. My friend Elizabeth agreed to initiate me to the Hoh. She had been in the forest many times and had spent time alone living in a tent near the forest. Her spiritual orientation to creation is what attracted me also. She did not see humans and nature as being separate. She knew the trees, the flowers, the streams, the paths. She led me to a special place along the Hoh River where warm black sands provided an exceptional meditative place.

Elizabeth taught me how to find nearby lodging so we could enter the forest twice in our visit. There is very limited camping in the Hoh Rain forest. It is part of the National Park system and one must possess a seasonal pass as well as a reservation to camp nearby. Even at the early part of the season, other people were present on the path-but they were few.

On our arrival to the park we entered the Hall of Mosses trail. I took a deep breath of the clean, fresh air. I looked up and saw the towering canopy of Big Leaf Maple, Sitka spruce,

Western Red Cedar and Western Hemlock. Some of the trees were near to 300 feet tall. All along the path the Redwood sorrel (Oxalis oregana) grew in large communities. We stopped to chew on a leaf. The citrus-like taste refreshed us both. Small nubs of soon-to-be wild flowers shot up through the leaf and winter debris layers. Although the weather was somewhat cool, the sun was out and the sunbeams shot down through the forest. It was a magical place and I am sure the Fae were present.

The cool moist landscape supported a community of unique lichen, ferns and fungi. Lettuce lichen (Lobaria oregana), grew on the sides of trees and downed logs and the forest floor. The Spike moss draped itself across the branches of the Big Leaf Maple.

Young Sitka Spruce grew from a downed nurse tree. These epiphyte flourish in Old Growth forests where generations of life lives and thrives one on top of the other.

We came upon a Black Cottonwood (Populus balsamifera) that was dropping it a sticky cone-shaped bud. The buds were fragrant with a balsamy scent. We realized we had come upon a coffer of the mystical Balm of Gilead. We picked up the sticky orange and gold coverings from the ground and inhaled the spicy scent. We understood that this bud contained a “salicylate precursors” related to aspirin and it was very healing. We shared stories about Balm of Gilead and how it is found on several other trees like the Balsam Poplar. We talked about how the sticky substance was used to line medicine bags of the First Peoples, both to protect healing plants and to keep out bad energy. We considered it a wonderful

find and put some in our pockets to soak at a later time.

We found native Willow growing along the Hoh river. There was both Pacific Willow (Salix lucida) and Scouler’s Willow (Salix scouleriana)present. I did not take any cuttings. This place is sacred and it is actually against the law to remove plants or plant materials from a National Park without permission. Also the Willow was sparse. Willow used to flourish in this area. The First People’s harvested it wisely for thousands of years. They used it to make baskets and hats and containers. They used it to patch housing and canoes and to make traps and fishing implements. Now it is very sparse. It should be left alone and respected or we will lose it. Such a gift.

I loved the sound of the Red-winged black bird as it sat in the tops of the Willow. The river current was swift as the spring melt from nearby glaciers filled the river banks. We could hear the Spruce grouse nearby calling for its mate. We saw an American Dipper in the nearby forest and a Bald Eagle soared overhead.

As we walked back to the Hall of Moss a young Roosevelt male Elk suddenly appeared on the trail some twenty feet away. We stood silently as it meandered along eating small

spring plants and sipping from a nearby stream. It walked into a nearby clearing and lay down. We very slowly moved away from the animal. Showing great respect for such a large wild animal is very prudent behavior. It did not show fear of us at all. Probably not a good strategy. Hunting may not be allowed now, but humans have a way of changing their wildlife “management” plans and have been known to slaughter what is beautiful (i.e. the buffalo of Yellowstone Park).

We saw quite an array of beautiful fungi protruding from every tree, rock and moss-covered ground. Most fungi obtain their food from dead organic matter (saprophytes). The multi-colored Conk’s and Turkey Tails splashed hues of gold, red, brown and yellow across the trunks of ancient trees. It was a glorious initiation into the deep woods.

My second excursion into the Hoh Rain Forest happened just weeks after the first. It was a mystical journey. This second trip was inspired in a most unusual way. In the week after the first, my dreams were filled with visions of the Hoh. In one dream I was called to come up a path and visit a teacher. The teacher was an unusual plant, one that I had not experienced before. It was tall, very tall with outreached branches. And it had large thorns. I was somewhat afraid of the plant that presented itself in my dream. I saw the thorns and thought “danger”. But instead it spoke to me about personal power and having good boundaries in this life. It spoke to me about the changes coming and how humans may act toward one another during these times. And, it asked me to go back to the Hoh Rain forest and find it. It did not tell me to harvest it, only find it and study it well because there was a life lesson to be found in finding it.

I did not even know what its name was so I contacted a herbalist I know who is deeply connected with the wild world. His name is Sean Donahue and he is a traditional herbalist who teaches in Victoria, British Columbia at Pacific Rim College in the Community herbalist program. He teaches herbal energetics. I heard him speak about some of the more powerful plants of the Olympic Peninsula and BC. And I was pretty sure he would know this plant and how to find it and maybe he would teach me about what the dream might mean. I sent him an email and also called him on the phone asking him about the plant. He immediately identified the plant as Oplopanax horridus or “Devils Club”. Sean told me that Devil’s club calls us to go into the deep murky places within us and to open up to those hidden parts. It helps shift people’s relationships to their grief, fear, pain, and sorrow, and reclaim their sense of self. Devil’s Club helps people reclaim their power and assert their right to be in the world.

I had gone through a time when I felt powerless. I had attracted energies into my life that threatened the safety of my very soul. Those others had been soul stealers and I had escaped only through prayer, energy healing and grace. Now I was scarred and at times so filled with grief that I could not move. I had become afraid to go into the forest by myself. My wonderful companion dog of 17 years had died and I had no way to sense my safety in the deep woods. Without my frequent trips to the deep woods I had lost my way to that which is sacred. I felt frozen. Sean said that an appearance of Devil’s club in ones dreams was a call to come back in the full power of the self. To honor one’s gifts and to step up ones spiritual journey.

I told him that the plant called me to go to the Hoh Rain Forest again and find it. Sean told me that he also wanted to go into the Hoh Rain Forest but had not had time to go since moving from the East Coast a year ago. So, I asked him if he would like to go with me. He said yes. And so we journeyed.

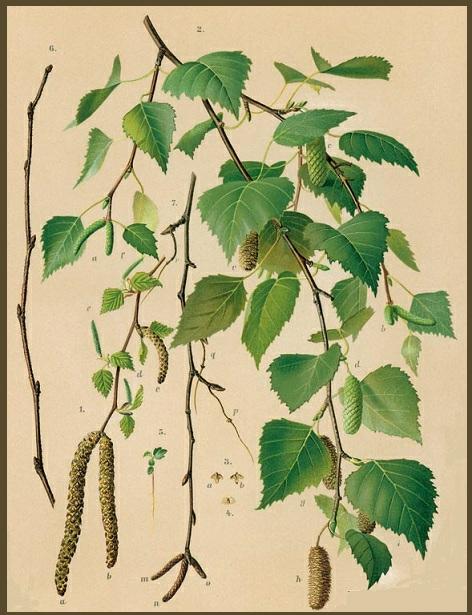

It was beautiful spring time weather. By this time in late April the wild flowers had begun to bloom and the sweet smell of the early blooming catkins of the Big Leaf Maple had been replaced by the heavier smell of Skunk Cabbage flowers, fungi blooms and green leaf. Salmonberry – (Rubus spectabilis) and Huckleberry (Vaccinium sp) were beginning to bloom. Sword fern unfurled along every trail. The streams were full of tiny young salmon (fry) that were being carried along the currents of the forest streams. The song of Robins filled the forest canopy.

There was a light rain that day as we proceeded down the Hall of Mosses. We walked for several miles. There was no sign of Devil’s Club. I wondered about that. I had expected to come upon it suddenly in a glen. But no, its appearance would be on its own terms. I asked several hikers if they had seen it. One man said you had to walk a good ten miles to see it and then it might be too early to see it with leaf. As we walked we saw many wondrous things. The Conk and Turkey Tail fungi we there in all their glory. The forest was a fairy land of fungi. The spring rains had awakened the fungi forest. The colors of the fungi ranged from violet to gold and red. The dark Chaga was tinged with violet and red. Small transparent fungi spread their skirts against the bright green moss.

Sean and I walked slowly through the forest looking at the magic of the place. We immersed ourselves in the community of nature fully intact. These are the days I live for. For nature is my true home, my mother and my family.

We had a wonderful day but we did not see Devil’s Club. I was somewhat let down. When I have these mini failures I begin to doubt my ability to connect with the higher forces, the angels and the Great Spirit Who Loves us all. Sean did a teaching for me. He taught me about the energetics of the Western Red Cedar. I love this tree. It is truly the central reason there is a rainforest here. This tree collects enough rain fall yearly to supply drinking water for a small village. It is a protector plant for thousands of other plants, animals, fungi and cloud cover.

I video-taped Sean’s teaching and will share it below:

Video of Sean Donahue talking about the medicine of the Western Red Cedar –

We left the Hoh Rainforest and headed back toward Port Angeles. On the outskirts of PA we decided to drive toward Hurricane Ridge and check out the flora. The ridge itself was still covered with snow. About a mile up the road Sean called out “stop! There it is…Devil’s club”. Sure enough the entire hillside along the road was covered in Devil’s Club. We drove down a side road exploring the plant life. The stream bed and bog along the road was covered in large yellow-flowered skunk cabbage. There were many Red Cedar and then we saw it. A very large Devil’s Club set back in the forest.

We got out and Sean began to teach again about the plant. He taught me about plant “signatures” and ask me look closely at the signature of this plant. I could see with its armor that indeed there was an air of boundary-making. Its branches somewhat outreaching and yet protective of the core of the plant. It stood out in its uniqueness and yet it had boundaries. There too was I. Always standing up and speaking out against injustice but then experiencing the crush of the status quo. I do believe that I do not have good boundaries with these people. I need to develop discernment. This is especially true in these ‘Changing Times”.

How the plant was used for medicine

The First People’s used the bark of this plant as a purgative . The bark was also used as a poultice for headache and pain. It was used to draw out rheumatism and aches. But it was also used to draw out toxins in the body via purging. A very powerful medicine on the physical level, and also used to draw out stagnant and stuck energy on the energetic level.

The medicine of this plant is so strong that a poultice was used to knit broken bones. So, it is…could the energetics of this plant knit back together my faith in humanity? Will I be assisted in my task of letting go of darkness so that I could continue on a path to self awareness and deep connection with the divine? Will I be able to help in this transition time? Can I serve? That is really all I want from this life? Is that too much to ask for. Devil’s Club says “Go deeper”.

References and Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Sean Donahue for letting me link to the video of his Western Red Cedar teaching. And for teaching me about our allies in the plant world.

Gunther, Erna. (1945) (Revised 1973) Ethnobotany of Western Washington. Knowledge and use of Indigenous plants by Native Americans, University of Washington Press.

Moerman, Daniel E.(1998) Native American Ethnobotany, Timber Press, Portland and London